PRETTY THINGS

Men’s fashion in Paris was moribund, but then Hedi Slimane came along.

by NICK PAUMGARTEN

Issue of 2006-03-20

Posted 2006-03-13

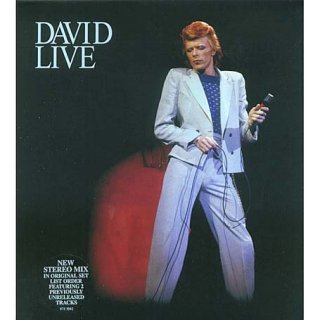

Hedi Slimane sits alone in his room, in a pleasant but not very fashionable part of Paris, mooning over an album cover. He has just turned six. The year is 1974. The record, a birthday gift from a friend of his older sister, is “David Live”—David Bowie, recorded at the Tower Theatre in Philadelphia. The friend, Véronique, likes to put on a blue jumpsuit and imitate Bowie. She does a good Mick Jagger, too. Slimane is captivated by her. He is also captivated by the album cover, which features a photograph of Bowie onstage, dressed in a powder-blue double-breasted suit: the jacket is cut short, with narrow but square shoulders, and the pants, although pleated and billowy in the legs, are tight at the crotch. Bowie looks bloodless and emaciated, well on his way to his “Thin White Duke” phase, during which he subsisted, as he later said, on “peppers, cocaine, and milk.”

Taste has to come from somewhere. Thirty years later, after Slimane has become a celebrated fashion designer who occasionally claims that he has no precedents or influences—who declares, “I have no nostalgia”—he allows that his sensibility owes a lot to “David Live” and to the early sight of this cool and cadaverous androgyne striking an angular pose. “When you’re a kid, you stare at things like this,” he says. “There is a moment of isolation in your room—a moment, maybe, of boredom.” There are many things that can contribute to a boy’s sense that another world exists out there, but, in 1974, nothing quite beat album covers, David Bowie, or older girls in blue jumpsuits.

Slimane designs menswear for Christian Dior, the venerable Paris fashion house. It is often said that he has transformed the male silhouette. Slimane’s clothes are generally made for and modelled by whip-thin young men, and among the tastemaking classes—rock stars, magazine editors, sugar daddies—the enthusiasm for his slender cuts has helped the scrawny lad displace the beefy gent as the body type of the age. (Slimane believes in what he once called a “morphology of decades.”) The extent to which this transformation has affected either the general public or the bottom line of LVMH, the company that controls Christian Dior and Slimane’s division, Dior Homme, is debatable, but such considerations hardly rate with the sophisticates who see him as a standard-bearer for a movement to infuse the old male armor—suits, tuxedos, jeans—with the insouciance and youth of rock and roll. “Some designers are more like stylists,” his friend Neil Tennant, of the pop band Pet Shop Boys, told me. “ ‘Heh-heh, they’re doing pirates.’ Or ‘disco New York.’ Hedi is one of those people who create a world.”

Hedi’s world is well edited and diligently curated, with the man himself at the center of it. You might say, although he wouldn’t, that he’s sort of a cross between Martha Stewart (everything just so) and Andy Warhol (anything’s possible). He is reticent and shy, and his pared-down approach to the presentation of himself applies also to the presentation of his work. He will not talk about a show beforehand, or even about what ideas or motifs are occupying his mind at the time, as they may relate to the clothes. He allows almost no one to visit his atelier, on Rue François 1er, in Paris. He doesn’t like to talk about a show when it’s over, either. He says that he can easily articulate what he is up to—he just prefers not to.

Fashion people talk for him. They describe his clothes as “modern,” “cerebral,” even “futuristic.” What such windy accolades reveal about a jacket is hard to say. Slimane also takes photographs, and designs furniture, and dabbles in architecture and graphic design, and his prevailing aesthetic is sleek and spare, but the clothes themselves are not merely minimal. They turn the sincere but desultory magpie style of a teen-age boy into high fashion, by means of the materials, proportions, and craftsmanship of couture. As a result, the clothes are a little challenging, as women’s clothes are.

Slimane’s menswear lines have drawn on the sartorial style of various movements in rock music, chief among them the recent revival of British guitar rock, which in turn harks back to the punk, glam, and post-punk eras of the seventies and early eighties. In turn, the bands that inspire him end up wearing his clothes: newer acts like Razorlight and Franz Ferdinand, mid-careerists like the White Stripes and Beck, and old-timers like Bowie and Jagger, who have become friends as well as clients.

Another hero of Slimane’s youth was Paul Simonon, of the Clash. When the Clash was admitted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, in 2003, Slimane had Dior send Simonon a couple of suits; he wore one of them to the induction ceremony. Simonon is an adherent of the idea that, as he put it, “you can’t have a situation where the audience dresses better than the group.” Soon afterward, Slimane went to Simonon’s studio, to photograph his bass guitar. They got on well. “I like narrow trousers,” Simonon explained. “I don’t like flares.”

Slimane, who met Bowie while out to dinner with (as he put it in an e-mail) “Boy Georges,” once asked him about “David Live.” Slimane told me, “I got the impression from him he didn’t like that album.”

Among the advances that have been attributed to Hedi Slimane is the hair style known as the “faux-hawk”—a coxcombical variation on the Mohawk, in which the hair is swept up toward the top from the sides. He says that he wound up with this haircut by accident, which is hard to believe, considering how particular he is. Hair stylists began to press it on their customers. It was eventually adopted by such widely photographed men as the soccer star David Beckham and the pop singer Robbie Williams, and by young urbanites, gay men, and celebrity toddlers around the world. Slimane abandoned his own faux-hawk when he encountered one on a desk clerk at a hotel in Prague.

Slimane’s most recent haircut has not been widely imitated. It consists of a wad brushed thickly forward over the top of his forehead and cropped straight across. It looks, frankly, a little like a toupee. Slimane’s friend Janet Street-Porter, the British writer and broadcaster, said, “He looks like a demented monk.”

It matters what Slimane looks like, because he is, in a way, his own best model. Being Hedi, he is the apotheosis of Hedi-ness. He has fine features and large, sad-seeming eyes and a melancholic expression that calls to mind Edward Scissorhands. He often furrows his brow. He is very slight, and he wears his clothes the way he would have others wear them: jeans low on the hips, jacket tight in the shoulders and short in the arms, silk scarf, Converse Chucks. Because he’s so thin and others would like to be, his eating habits are a source of curiosity. He says that he eats baby food, and some stories have suggested that he hardly eats at all. But the fashion designer who can do without food is a mythical beast, like the business executive who never sleeps. (Slimane’s friend and mentor Karl Lagerfeld supposedly survives on Pepsi Max, and has said that the reason he lost eighty pounds, not long ago, was to fit into clothes designed by Slimane.) “Hedi eats loads,” Street-Porter told me. Tennant recalled, “One time at his hotel in London, Hedi had chicken goujons as a starter. Then, for his main course, he had a larger portion of chicken goujons. I told him I thought this was strange, and he said, ‘But they’re very good.’ ” Slimane doesn’t drink, smoke, or do drugs. He merely fetishizes the appearance of those who do.

“When I was a teen-ager, people used to comment on how dreadfully skinny I was,” Slimane told me. “I used to take pills to put on weight.” Since no clothes fit him, he began designing his own. His mother was a seamstress, so he knew his way around a sewing machine. “I also always thought clothes looked better on a lean figure,” he said. “Life was not that unfair after all. There was a future for skinny people.”

Slimane was born in Paris and grew up in the Buttes-Chaumont district. His father, who is Tunisian and a retired accountant, had been a boxer in Bordeaux (poids léger, of course), and he met Hedi’s mother, an Italian, when she was working as a coat-check girl in a club in Saint Germain des Près. (“He won her over with a great dance,” Slimane told me.) He hardly keeps in touch with them. In his early teens, he spent vacations with an uncle who lived in Geneva and hung out with a “free-spirited” cousin and her brother, “who was quite the opposite,” Slimane said. “Something like the Patrick Bateman character in ‘American Psycho.’ I was stuck between indie kids and call girls, squats and palace hotels.”

After high school, Slimane studied art for three years and then began helping friends on fashion shoots and shows, as a freelance art director and casting scout. In the early nineties, he spent a couple of penniless but fond years in New York, going to night clubs with Stephen Gan, who is now the creative director of Harper’s Bazaar and the editor of Visionaire, and passing through phases, including a haut-preppy stage, in which, as Gan recalls, he insisted on the “perfect polo shirt, the perfect khakis.” One day, doing fittings for a friend’s fashion show, Slimane was noticed by the LVMH consultant and talent-trawler Jean-Jacques Picart, who on a hunch hired him as his assistant. Three years later, Pierre Bergé, the C.E.O. of Yves Saint Laurent, and Saint Laurent’s longtime companion, noticed Slimane, too—actually, he’d merely heard about him—and tapped him to be the menswear designer at Yves Saint Laurent, even though he had very little experience or training. “All of a sudden, Hedi was designing,” Gan said. “It was a fluke.”

Saint Laurent’s menswear line was moribund at the time. “Milan was menswear, and French houses were not interested in men’s fashion,” Slimane said. “To hire me was an insignificant decision, if you think in concrete terms. But, from a different perspective, I really had as a kid a natural attraction to the house of Saint Laurent, and when Pierre Bergé took the chance I thought I was extremely blessed. I remember sitting down in his stunning office on the Avenue Marceau, totally petrified. It didn’t last more than ten minutes. I just went straight to the atelier a couple of days later, walking on tiptoes, and designed my first collection.”

It took him a few seasons to start doing things the way he wanted to. By 1998, he was attracting acclaim. Then, in 1999, Gucci took over Y.S.L., which meant that Slimane would have a new boss: Tom Ford, the creative director at Gucci, who insisted that Slimane report to him. “It was a totally new idea to me, this story of ‘reporting,’ ” Slimane told me. (His English is good but not perfect.) “I might have never heard the word ‘reporting’ before. Reporting to Tom was not going to happen.” Bergé objected to the arrangement, too. “I was absolutely against it,” he told me. “Tom Ford is not my cup of tea. I don’t respect him, not at all. He is not a designer. He is a marketing man.” After meeting with Ford at the Ritz (“The situation became unpleasant,” Slimane said), Slimane resigned.

Men’s fashion in Paris was moribund, but then Hedi Slimane came along.

by NICK PAUMGARTEN

Issue of 2006-03-20

Posted 2006-03-13

Hedi Slimane sits alone in his room, in a pleasant but not very fashionable part of Paris, mooning over an album cover. He has just turned six. The year is 1974. The record, a birthday gift from a friend of his older sister, is “David Live”—David Bowie, recorded at the Tower Theatre in Philadelphia. The friend, Véronique, likes to put on a blue jumpsuit and imitate Bowie. She does a good Mick Jagger, too. Slimane is captivated by her. He is also captivated by the album cover, which features a photograph of Bowie onstage, dressed in a powder-blue double-breasted suit: the jacket is cut short, with narrow but square shoulders, and the pants, although pleated and billowy in the legs, are tight at the crotch. Bowie looks bloodless and emaciated, well on his way to his “Thin White Duke” phase, during which he subsisted, as he later said, on “peppers, cocaine, and milk.”

Taste has to come from somewhere. Thirty years later, after Slimane has become a celebrated fashion designer who occasionally claims that he has no precedents or influences—who declares, “I have no nostalgia”—he allows that his sensibility owes a lot to “David Live” and to the early sight of this cool and cadaverous androgyne striking an angular pose. “When you’re a kid, you stare at things like this,” he says. “There is a moment of isolation in your room—a moment, maybe, of boredom.” There are many things that can contribute to a boy’s sense that another world exists out there, but, in 1974, nothing quite beat album covers, David Bowie, or older girls in blue jumpsuits.

Slimane designs menswear for Christian Dior, the venerable Paris fashion house. It is often said that he has transformed the male silhouette. Slimane’s clothes are generally made for and modelled by whip-thin young men, and among the tastemaking classes—rock stars, magazine editors, sugar daddies—the enthusiasm for his slender cuts has helped the scrawny lad displace the beefy gent as the body type of the age. (Slimane believes in what he once called a “morphology of decades.”) The extent to which this transformation has affected either the general public or the bottom line of LVMH, the company that controls Christian Dior and Slimane’s division, Dior Homme, is debatable, but such considerations hardly rate with the sophisticates who see him as a standard-bearer for a movement to infuse the old male armor—suits, tuxedos, jeans—with the insouciance and youth of rock and roll. “Some designers are more like stylists,” his friend Neil Tennant, of the pop band Pet Shop Boys, told me. “ ‘Heh-heh, they’re doing pirates.’ Or ‘disco New York.’ Hedi is one of those people who create a world.”

Hedi’s world is well edited and diligently curated, with the man himself at the center of it. You might say, although he wouldn’t, that he’s sort of a cross between Martha Stewart (everything just so) and Andy Warhol (anything’s possible). He is reticent and shy, and his pared-down approach to the presentation of himself applies also to the presentation of his work. He will not talk about a show beforehand, or even about what ideas or motifs are occupying his mind at the time, as they may relate to the clothes. He allows almost no one to visit his atelier, on Rue François 1er, in Paris. He doesn’t like to talk about a show when it’s over, either. He says that he can easily articulate what he is up to—he just prefers not to.

Fashion people talk for him. They describe his clothes as “modern,” “cerebral,” even “futuristic.” What such windy accolades reveal about a jacket is hard to say. Slimane also takes photographs, and designs furniture, and dabbles in architecture and graphic design, and his prevailing aesthetic is sleek and spare, but the clothes themselves are not merely minimal. They turn the sincere but desultory magpie style of a teen-age boy into high fashion, by means of the materials, proportions, and craftsmanship of couture. As a result, the clothes are a little challenging, as women’s clothes are.

Slimane’s menswear lines have drawn on the sartorial style of various movements in rock music, chief among them the recent revival of British guitar rock, which in turn harks back to the punk, glam, and post-punk eras of the seventies and early eighties. In turn, the bands that inspire him end up wearing his clothes: newer acts like Razorlight and Franz Ferdinand, mid-careerists like the White Stripes and Beck, and old-timers like Bowie and Jagger, who have become friends as well as clients.

Another hero of Slimane’s youth was Paul Simonon, of the Clash. When the Clash was admitted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, in 2003, Slimane had Dior send Simonon a couple of suits; he wore one of them to the induction ceremony. Simonon is an adherent of the idea that, as he put it, “you can’t have a situation where the audience dresses better than the group.” Soon afterward, Slimane went to Simonon’s studio, to photograph his bass guitar. They got on well. “I like narrow trousers,” Simonon explained. “I don’t like flares.”

Slimane, who met Bowie while out to dinner with (as he put it in an e-mail) “Boy Georges,” once asked him about “David Live.” Slimane told me, “I got the impression from him he didn’t like that album.”

Among the advances that have been attributed to Hedi Slimane is the hair style known as the “faux-hawk”—a coxcombical variation on the Mohawk, in which the hair is swept up toward the top from the sides. He says that he wound up with this haircut by accident, which is hard to believe, considering how particular he is. Hair stylists began to press it on their customers. It was eventually adopted by such widely photographed men as the soccer star David Beckham and the pop singer Robbie Williams, and by young urbanites, gay men, and celebrity toddlers around the world. Slimane abandoned his own faux-hawk when he encountered one on a desk clerk at a hotel in Prague.

Slimane’s most recent haircut has not been widely imitated. It consists of a wad brushed thickly forward over the top of his forehead and cropped straight across. It looks, frankly, a little like a toupee. Slimane’s friend Janet Street-Porter, the British writer and broadcaster, said, “He looks like a demented monk.”

It matters what Slimane looks like, because he is, in a way, his own best model. Being Hedi, he is the apotheosis of Hedi-ness. He has fine features and large, sad-seeming eyes and a melancholic expression that calls to mind Edward Scissorhands. He often furrows his brow. He is very slight, and he wears his clothes the way he would have others wear them: jeans low on the hips, jacket tight in the shoulders and short in the arms, silk scarf, Converse Chucks. Because he’s so thin and others would like to be, his eating habits are a source of curiosity. He says that he eats baby food, and some stories have suggested that he hardly eats at all. But the fashion designer who can do without food is a mythical beast, like the business executive who never sleeps. (Slimane’s friend and mentor Karl Lagerfeld supposedly survives on Pepsi Max, and has said that the reason he lost eighty pounds, not long ago, was to fit into clothes designed by Slimane.) “Hedi eats loads,” Street-Porter told me. Tennant recalled, “One time at his hotel in London, Hedi had chicken goujons as a starter. Then, for his main course, he had a larger portion of chicken goujons. I told him I thought this was strange, and he said, ‘But they’re very good.’ ” Slimane doesn’t drink, smoke, or do drugs. He merely fetishizes the appearance of those who do.

“When I was a teen-ager, people used to comment on how dreadfully skinny I was,” Slimane told me. “I used to take pills to put on weight.” Since no clothes fit him, he began designing his own. His mother was a seamstress, so he knew his way around a sewing machine. “I also always thought clothes looked better on a lean figure,” he said. “Life was not that unfair after all. There was a future for skinny people.”

Slimane was born in Paris and grew up in the Buttes-Chaumont district. His father, who is Tunisian and a retired accountant, had been a boxer in Bordeaux (poids léger, of course), and he met Hedi’s mother, an Italian, when she was working as a coat-check girl in a club in Saint Germain des Près. (“He won her over with a great dance,” Slimane told me.) He hardly keeps in touch with them. In his early teens, he spent vacations with an uncle who lived in Geneva and hung out with a “free-spirited” cousin and her brother, “who was quite the opposite,” Slimane said. “Something like the Patrick Bateman character in ‘American Psycho.’ I was stuck between indie kids and call girls, squats and palace hotels.”

After high school, Slimane studied art for three years and then began helping friends on fashion shoots and shows, as a freelance art director and casting scout. In the early nineties, he spent a couple of penniless but fond years in New York, going to night clubs with Stephen Gan, who is now the creative director of Harper’s Bazaar and the editor of Visionaire, and passing through phases, including a haut-preppy stage, in which, as Gan recalls, he insisted on the “perfect polo shirt, the perfect khakis.” One day, doing fittings for a friend’s fashion show, Slimane was noticed by the LVMH consultant and talent-trawler Jean-Jacques Picart, who on a hunch hired him as his assistant. Three years later, Pierre Bergé, the C.E.O. of Yves Saint Laurent, and Saint Laurent’s longtime companion, noticed Slimane, too—actually, he’d merely heard about him—and tapped him to be the menswear designer at Yves Saint Laurent, even though he had very little experience or training. “All of a sudden, Hedi was designing,” Gan said. “It was a fluke.”

Saint Laurent’s menswear line was moribund at the time. “Milan was menswear, and French houses were not interested in men’s fashion,” Slimane said. “To hire me was an insignificant decision, if you think in concrete terms. But, from a different perspective, I really had as a kid a natural attraction to the house of Saint Laurent, and when Pierre Bergé took the chance I thought I was extremely blessed. I remember sitting down in his stunning office on the Avenue Marceau, totally petrified. It didn’t last more than ten minutes. I just went straight to the atelier a couple of days later, walking on tiptoes, and designed my first collection.”

It took him a few seasons to start doing things the way he wanted to. By 1998, he was attracting acclaim. Then, in 1999, Gucci took over Y.S.L., which meant that Slimane would have a new boss: Tom Ford, the creative director at Gucci, who insisted that Slimane report to him. “It was a totally new idea to me, this story of ‘reporting,’ ” Slimane told me. (His English is good but not perfect.) “I might have never heard the word ‘reporting’ before. Reporting to Tom was not going to happen.” Bergé objected to the arrangement, too. “I was absolutely against it,” he told me. “Tom Ford is not my cup of tea. I don’t respect him, not at all. He is not a designer. He is a marketing man.” After meeting with Ford at the Ritz (“The situation became unpleasant,” Slimane said), Slimane resigned.

...raf is turning into quite the media wh*re these days himself...

...raf is turning into quite the media wh*re these days himself... ...

...

...

... ...

...